It is April 26th. As I watched the evening news last night, it hit me: It’s been a year since the great catastrophe that devastated parts of Nepal, the small country clinging precariously to the foothills of the Himalayas. The earthquake (or rather quakes) left one of the poorest countries on the planet in an impossible situation. Unfortunately, it is painfully obvious that the rebuilding process is not on track and most of the displaced and the homeless still live in temporary shelters. I was part of the relief effort last year working at the Norwegian Red Cross Field hospital at Chautara for a month. The question I cannot help to ask is: Have we failed?

I didn’t write about my stay in Nepal when I returned home ten months ago and I have put it on hold since. I’m not really sure why. There have been lots of other things on my mind and I was optimistic about the prospects of rebuilding the country and it felt redundant somehow. I feel bad about it now, since the way things have turned out, keeping Nepal on people’s minds is important. So this is my belated contribution.

Field School

I came to Nepal for the first time in 2011 as a delegate for the Red Cross Field School training course. The purpose was to practice under realistic circumstances the evaluation processes that are so vital in the first chaotic days of a disaster, when the acute needs of the affected population need to be quickly assessed in order to deploy the right kind of help to the people that need it most. It’s not really rocket science, what people hit by a natural disaster usually need is food, shelter, clean water and sanitation facilities that prevent the spread of diseases, medical help and psycho-social support. But in the history of disaster relief quite a few blunders have occurred, so that training and standardization appear to be an obvious way to go forward. Good intentions alone are insufficient when you have to launch a quick and intelligent response. As the saying goes: The way to hell is paved with good intentions. In a way, disaster relief is a bit like surgery: You know that you will inflict harm, but in the end you’ll have to make sure that the benefits outweigh the harms. Just doing something, anything, isn’t good enough.

Field School training 2011, Chitwan Province, Nepal

The two weeks at field school in Chitwan province were among the most exhausting of my life. The drills, and the tasks, and the dead lines pushed me constantly out of my comfort zone, and in the end I left humbled by the experience and acutely aware of the fact that no matter how well prepared you are, mistakes and blunders and miscalculations will happen. Such is the nature of an unforeseen disaster. And I left with a deep respect for the people of Nepal who by and large have to make their livelihoods from nothing. My hope was, that nature would leave Nepal alone; that it would not add insult to injury; that we would not have to put our training to the test here. It was not to be.

My friend Sushil from Nepal Red Cross doing one of his hygiene promotions. It is quite a performance and the villagers are spellbound. He is absolutely brilliant. Field School training 2011, Chitwan Province, Nepal

April 2015. The mountains tremble

Rumors traveled quickly on this 25th of april 2015. Still at work, I was told that Nepal had been hit, and hit hard. With a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale, an earthquake had shaken the country violently, lasting for about fifty seconds. It was the worst earthquake in the region since the 1930’s. Watching in disbelief the video footage from the quake, my first thoughts went out to my friends in Nepal, friends I had made at Field School: Sushil, Jagadish, Dinesh and the others; were they all right? Had they and their families made it? It was through social media channels that it quickly became clear that they were. Facebook released a ‘Safety Check’ feature, and one by one they called in safe. It was a great relief. Most of them were camping in the streets, though, afraid of the after shocks that kept coming.

Twenty-four hours later, on a Sunday, the expected voice message from Norwegian Cross came: They were going to deploy the field hospital and everyone was asked to check their availability. I was itching to go. This disaster was personal. It felt wrong staying behind. Unfortunately it soon became clear that I had to, at least initially. Norwegian hospitals have a proud tradition of deploying doctors and nurses for international relief efforts, my colleagues are usually prepared to cover for me, but for the first three weeks of the deployment, I was indispensable at work. It was a tough reality to face, but for the first weeks I would have to follow my fellow Red Cross delegates on Facebook and the news.

Deployment

On the May 27 it is finally my turn. I have my briefing on the telephone, there is no time for a trip to headquarters in Oslo and I basically go straight from work to the airport. This time I have to travel alone. No Kirsti to talk to, like last time, when the destination was Basey on the Philippines. On the way to Kathmandu I have a seven hour stop-over at Delhi airport and I hire one of these funny little cabins with a bed, located in the transit zone in order to get some sleep, but I just end up staring at the ceiling. I’m not really nervous, but I just want to get to my destination as quickly as possible. Sleep feels like an unwelcome interruption, a delay.

When my plane finally breaks through the clouds over Kathmandu, my thoughts go back to Field School again: When we flew out from Kathmandu three years earlier, I remember looking at the skyline, with its tall buildings, all built according to rules that no engineer has ever approved, and which all seemed to have been raised on an area the size of a stamp. And I remember thinking: If an earth quake ever hits this city, the result will be complete and utter destruction. So as my plane descends towards Tribhuvan International Airport, I anxiously screen the city through my window and I’m in for a surprise: Most of the city and the buildings which I had assumed would tumble like card houses are still standing! It is a pleasant surprise, but -as I soon realize- a bit of a problem, too. World media representatives, who probably have their own machinery of initial disaster assessment and who had descended in legions on Kathmandu after the earth quake, had taken a quick and hard look at the city and decided that this wasn’t too bad after all – and they had left. Off to the next crisis. I had noticed back home that Nepal had disappeared from the headlines suspiciously fast . The lack of media attention and the declining news coverage convey the message to the world that everything is all right, or at least under control.

Destruction at Dunbar square in the heart of Kathmandu, June 2015. But like many other buildings in the city quite a few of the temples have survived the quake, damaged but not broken.

I know better. I know that Kathmandu is not representative for the country as a whole, where the majority of the population has rather slim odds for survival even in the best of times. I know that they will be struggling badly in the aftermath of this catastrophe. I know they will need all the help they can get. That the eyes of the world have turned away so quickly is letting them down.

Chautara

There are some hiccups with my transport but I eventually manage to catch a Landrover which carries me to my destination: Chautara, located in the mountains east of Kathmandu and the district capital of the province of Sindhupalchowk. The epicenter of both earth quakes has been close by and the area is one of the most affected in the country. And yes, there has been another quake on May 12th, wreaking further havoc and destruction.

Entering an area hit by an earth quake is a depressing experience. As I will soon find out myself, the earth keeps trembling, almost every day. Minor quakes, of course, but still a constant reminder for the hard-tried population that worse may still be in store. Chautara is located at 1500 meters above sea level and this may have had an impact on the amplitude of the movements of the earth. Almost like being on the end of a moving stick versus being at the bottom. I don’t know if this a correct description of the physics involved, but some buildings have literally been whipped off the crest of the mountain that Chautara is built on.

When we enter the town I can read the frustration in every face we pass. I can sense the great questions plaguing them: What is the point in rebuilding, when the next quake will bring everything down again? Are the temporary shelters sufficient for survival when the monsoon arrives? Will we be able to sustain our families?

Houses have been smashed, moved, bent and cracked. The majority of buildings are too damaged to serve as accommodation. May 2015, Chautara, Nepal.

A Japanese team of earth quake experts has assessed the damage in Chautara. They have left color marks on every building. Green means that the building can be used safely. Red means that entering is dangerous. There is far more red than green.

Chautara from a distance. The only sign that this is a place in dire straits and not paradise are the many temporary shelters dotting the landscape

On one of my first evenings I go for a little walk and I realize how beautiful Chautara must have been. How beautiful the view is. Wherever I look I can see these hills that flow like green and endless waves towards the white and majestic chain of mountains in the distance which is the Himalaya.

And this, I think, is the difference between them and us: We have the luxury of admiring the beauty of nature. For us nature is something to be loved and enjoyed and idealized. For them nature is a mortal threat. To be feared and endured. From where I stand this evening, I get to see both: The beauty. And the cruelty.

The view from a ruined town: The Himalaya in the distance

Work

An advantage of not being on the first rotation is that everything is in place. Routines are established and you basically do what you are trained to do every day. The field hospital has been admitting the first patients only a week after the first earth quake which is quite a remarkable feat considering that everything had to be flown in from Norway, transferred to lorries in Kathmandu and then transported to Chautara on narrow and damaged mountain roads. Norwegian Red Cross has done this countless times before and also in this instance everything has worked smoothly. The hospital has been operational when the second earth quake hit and everyone on the staff did a great job with the inflow of the injured and the sick. Several more buildings have collapsed in Chautara, among them the hotel.

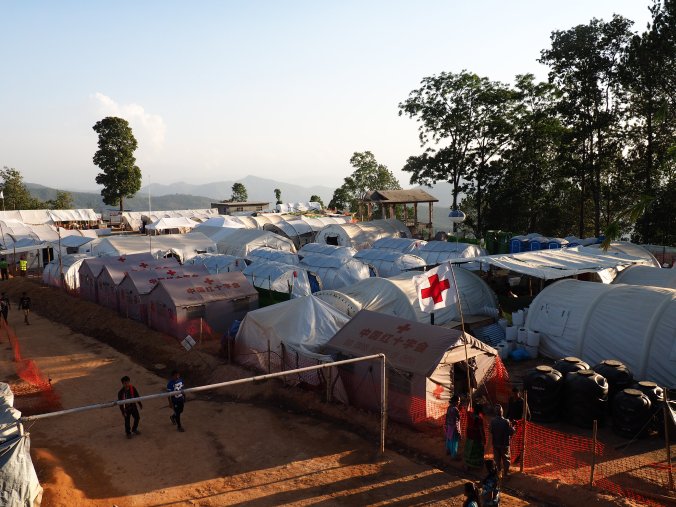

Norwegian Field Hospital, Chautara, Nepal

The first team has done a marvelous job with the hospital set-up which is close to perfect. It is located on an athletic field which is the only level area as far as the eye can see in this landscape of mountains. Several other NGO’s are crowded into the same space, but it’s the Norwegian Field Hospital which is the main actor there. The district hospital just down the road has been badly damaged which means that the local doctors work together with us at the field hospital. They are a pleasant bunch and very competent. They don’t want us to do routine surgery, however, as this might raise expectations in a population which will have to do without surgeons when we leave. So we limit us to emergency surgery and wound and fracture treatment. There is enough to take care of.

Borghild and I debriding an old leprosy wound. We learn that turpentine is a useful agent against maggots

One of the great privileges of going on a mission is the people you meet, both local and international, and after just a couple of days the team feels like family. The team in Chautara consists of delegates from Norway, Hongkong, Canada, Iceland, Sweden and Lesja (an isolated colony of outcasts in the middle of Norway). It is touching to see so many good people giving their best under difficult circumstances. It is at times like these that you witness humanity at its best.

The Expat team. June 2015, Chautara, Nepal

The people

I am the only surgeon at the hospital, but since radio cover is generally good I can go on little walks every now and again. It gives me a better picture of the area and I get a close look at how the most disadvantaged people of the area live and cope after the quake. The main conclusion is: They are not doing too well. There are clearly distribution issues and some still haven’t received their tarpaulins almost six weeks after the first quake. And the first signs of the coming monsoon are unmistakable hints that grave difficulties lie ahead for those who have little. Most houses outside Chautara are of inferior quality and have been built partly without cement. People simply cannot afford it. Few of the houses have been a match for earthquakes.

A family sitting in front of the remnants of their home. A village outside Chautara, Nepal, June 2015

I also realize that this is the sort of environment I have to send my patients back to.Patients with surgical wounds, patients with open wounds. It’s not like at home where they are attended to by mobile nursing services and where there wound dressings are changed under sterile conditions. Here they have to recover in ruins, inadequately sheltered from the rain; mud and dust everywhere. It is in these surroundings they get their wounds in the first place, digging in the rubble with their bare hands, bare-feet or with just sandals which have seen better days.

In the beginning we give our patients tents when they are discharged. Then reports come in that this has created tensions in communities where everyone is without adequate shelter. Apparently, there have even been attacks. This shows how difficult it is to get it right. And again, good intentions don’t automatically make for good solutions. As a consequence I choose to have patients at the hospital for longer than strictly necessary. But also this solution has its draw-backs: I deprive families of a helping hand. Sometimes it feels like you can’t win. Sometimes you just have to choose between two evils.

Right now this experience feels like a reflection of the current situation and the stalled rebuilding process: In search of a perfect solution where you try to make everyone happy, you quickly end up with no solution at all. Maybe a sub-optimal solution is the best one can hope for? Nepal and its people are used to sub-optimal solutions and will probably handle it well.

Collecting fresh and clean water at the water hub. The water is brought by trucks. People (and that means mostly women) collect the water in containers and often have to carry it for miles to their homes. June 2015, Chautara, Nepal

Leaving

Everything comes to end and after four weeks it is my turn to leave the bubble. And being on a mission is like living in a bubble where you quickly adapt to a very different reality. I cry like a baby when I say my good-byes. Iblame it all on Vidar, our Senior Medical Officer and GP, who definitely started the whole crying business.

Leaving (photo by Sherry Humphrey)

I leave with the feeling that it has been a good mission, that we have made a difference and that we have given help and comfort to a hard-tried population. I hope that the majority of the people of Chautara feel that our presence has been a positive thing for them, although one can never be sure. A lot remains to be done and the rebuilding process is quite obviously a thing that is not going to happen overnight. But I feel optimistic. I feel that things will turn out all right.

The district hospital is starting to function again and in a couple of weeks we will be superfluous here, which is a good thing. Although Nepal is a poor country they have a well-functioning health system which will be able to cope again with the situation, after the shocks of the quake are absorbed.

In Kathmandu I get to meet my old friend Sushil from Field School days again and he invites me to his home where I get to meet his wife and kid. They are lovely people and I feel privileged to have them as friends. In the evening it is reunion time with the rest of the old Delta Team. We weren’t really any good at Field School compared with the other teams but we have surely kept in touch! And that is an outstanding performance after all.

Delta team reunion: Dinesh, Jagadish, Sushil and I. June 2015, Kathmandu, Nepal

Sushil tells me that he has to think about moving and working abroad like so many other Nepalese (remittances are Nepal’s largest source of income). The quake has left many with a feeling of insecurity; the feeling that their home country, their place of birth and the land of their ancestors, may not be a good place to live anymore and to raise your children. I can feel a lump in my throat. The statistics show that emigration has soared indeed during the last twelve months with long-term consequences for the country which are unclear at best.

And now what?

The anniversary of the great tragedy has brought media attention back to Nepal and the common theme of articles and news reels are that somehow the process of rebuilding is in trouble. While still hundreds of thousands of Nepalese huddle under tarpaulins, billions of pledged dollars are sitting idly, waiting to be put to use. This can’t be good. When Norwegian Television returned to Chautara, the place where our field hospital was located, they felt unwelcome. People were clearly sick of white people coming and then leaving while their most essential need -the rebuilding of their homes- is still unmet. I can feel my optimism from a year ago crumble. Will this be one of these events where you win a great battle and lose the war anyway? The disaster relief a year ago was by and large a success and all the training and all the preparations proved to have been a good investment. But how can one train for the rebuilding of a country? The just allocation of money and resources? The fixing of the long-term consequences of a natural disaster?

The tedious political processes around the rebuilding effort are complicated and probably necessary and have to some degree be respected and endured. On the other hand, the large amounts of donor money that are currently unused and the continuous suffering of the people affected by the earth quake a year ago, should be a strong reminder to all parties involved that something actually has to happen. And it probably has to happen soon, before the next monsoon season will make itself felt. It may not be as “mild” as the last one. My hope is that wisdom and an acute sense for what is necessary will prevail. Let’s settle for a sup-optimal solution with a sub-optimal use of the donations. We owe it to the people of Nepal.

The views expressed in this article reflect the authors opinion alone. They do not in any way represent the view of Norwegian Red Cross or the International federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

Please visit my other blogs:

A Hundred Thousand Bethlehems – The refugee crisis in Bangladesh

THE PHILIPPINES AFTER YOLANDA- PART 1

THE PHILIPPINES AFTER YOLANDA – Part 2

THE PHILIPPINES AFTER YOLANDA – PART 3

Prostate Cancer for Dummies- Part 1: Basics

Prostate Cancer for Dummies-Part 2: the PSA

Dr Vidar , we really proud of you and norwegain redcross to help an earthquake affected people in chautara that was great job of yours . We could not imagine that what would happen if field hospital was not provided the treatment to injured people so the injure people is still alive due to yours greatness . Thanks once again. And the matter of rebuilt–it is being delay due to indian blocked and some internal political problem if nepal government have enough money. So we hope that we can rebuilt good and safe shelter ni future and nepal government have declear that the country have fulfill the rebuilt process within 4 years the number of eight lakh homes and nine thousands school .thanks for your great articles sir Vidar.

Pingback: The Front Line Guide To Prostate Cancer -Part 2: PSA | Journeys in Medicine

Pingback: Prostate Cancer for Dummies- Part 1: Basics | Journeys in Medicine

Pingback: A Hundred Thousand Bethlehems | Journeys in Medicine

Pingback: THE PHILIPPINES AFTER YOLANDA- PART 1 | Journeys in Medicine

thanks